The Daugava River (Dúna in Old Norse), to which mouth arise Riga, has been a trade route since around the sixth century AD, when Viking explorers crossed the Baltic Sea, navigating upriver into the Baltic interior. In medieval times the Daugava was an important navigation trading route for transport of furs from the north and Byzantine silver. The Riga area was a key element of settlement and defence of the mouth of the Daugava at least as early as the Middle Ages, as evidenced by the now destroyed fort at Torņakalns on the west bank of the Daugava at present day Riga.

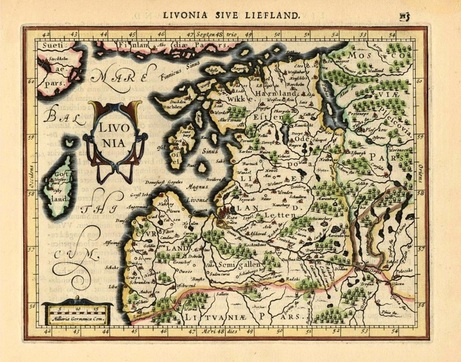

Riga was born in a sheltered natural harbor 15 km upriver from the mouth of the Daugava. It has been recorded as an area of settlement called the "Duna Urbs", as early as the 2nd century, when ancient sources already refer to Courland as a kingdom. During the 5th and 6th centuries, about the same time that Riga began to develop as a center of Viking trade, it was settled by the Livonians, an ancient Finnic tribe. They occupied themselves mainly with crafts in bone, wood, amber, and iron; fishing, animal husbandry, and trading. The "Chronicle of Henry of Livonia" mentions Riga's earliest recorded fortifications upon a promontory, Senais Kalns ("Ancient Hill"). It also testifies to Riga having long been a trading center by the 12th century, referring to it as portus antiquus (ancient port), and describes dwellings and warehouses used to store mostly corn, flax, and hides.

The origin of the name of Riga is related to its already. Established role in commerce between East and West, as a borrowing of the Latvian "rija". The origin of Riga from rija is confirmed by the German historian Dionysius Fabricius (1610): "The name Riga is given to itself from the great quantity which were to be found along the banks of the Duna of buildings or granaries which the Livonians in their own language are wont to call Rias." |

German traders began visiting Riga and its environs with increasing frequency toward the second half of the 12th century, via Gotland. Bremen merchants shipwrecked at the mouth of the Daugava established a trading outpost near Riga in 1158. Christianity had established itself in Latvia more than a century earlier with a church built in 1045 by Danish merchants. Orthodox Christianity being brought to central and eastern Latvia by missionaries. The monk Meinhard of Segeberg, arrived from Gotland in 1184. Many Latvians had been already baptised prior to Meinhard's arrival. Meinhard's mission, nevertheless, was no less than mass conversion of the pagans to Catholicism. He settled among the Livonians of the Daugava valley at Ikšķile, about 20 km upstream from Riga. With their assistance and promise to convert, he built a castle and a church of stone—a method heretofore unknown by the Livonians and of great value to them in building stronger fortifications against their own enemies. Hartwig II, Prince-Archbishop of Bremen, was eager to expand Bremen's power and properties northward and consecrated Meinhard as Bishop of Livonia (from the German: Livland) in 1186, with Ikšķile as bishopric. When the Livonians decided not to give up their pagan ways, Meinhard grew impatient and plotted to convert them forcibly. The Livonians, however, thwarted his attempt to leave for Gotland to gather forces, and Meinhard died in Ikšķile in 1196, having failed his Imperialist mission. Hartwig II appointed abbot Berthold of Hanover—who may have already traveled to Livonia — as Meinhard's replacement. In 1198 Berthold arrived with a large contingent of crusaders and commenced a campaign of forced Christianization. A Latvian legend tells that Berthold, galloping ahead of his forces in battle, was surrounded and drew back in fright as someone realizing they have stepped on a snake, at which point the Lionianv warrior Imants struck and speared him to death. Ecclesiastical history faults Berthold's unruly horse for his untimely demise.

The Church, continuing its traditional imperialist policy, mobilized to avenge Berthold's death and the defeat of his forces. Pope Innocent III issued a papal bull declaring a crusade against the Livonians, promising forgiveness of sins to all participants. Hartwig II consecrated his nephew, Albert, as Bishop of Livonia in 1199. A year later, Albert landed in Riga with 23 ships and 500 Westphalian crusaders.

|

Thus, Henry of Livonia, described the horrors suffered by the Livonians after a day of battle against the crusaders: "On the following day, after all the villages had been colored with much pagan blood, they returned. Collecting many spoils from the villages, they took back with them the beasts of burden, many flocks and a great many girls, whom alone the army was accustomed to spare in these lands."

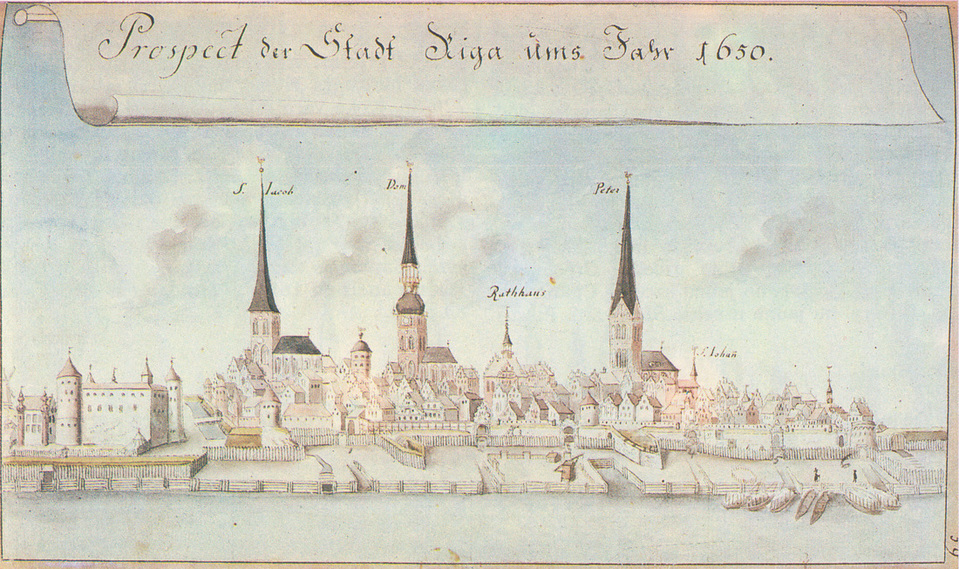

In 1201 Albert transferred the seat of the Livonian bishopric from Ikšķile to Riga. In the present day, 1201 is still celebrated as the founding of Riga by Albert—integral to the "bringer of culture" myth created by later German and ecclesiastical historians. This imperialist myth tells how Germans discovered Livonia and brought "civilization" and "religion" to the virulently anti-Christian pagans.

Albert established ecclesiastical rule and introduced the Visby code of law. To insure his conquest and defend German merchant trade, the monk Theodoric of Estonia established the Order of Livonian Brothers of the Sword (Fratres Militiae Christi Livoniae, "Order") open to both nobles and merchants. Church history relates that the Livonians were converted by 1206. The first prominent Livonian converted was Caupo of Turaida, a leader of Livonian peoples, sometimes called "The King of Livonia". He was probably baptized around 1191 by the priest Meinhard. He became an ardent Christian and friend of Albert, who took him (1203-1204) on the way to Rome and introduced him to Pope Innocent III. The Pope was impressed by the converted pagan chief and presented him a Bible.

When he returned from travel, his tribe rebelled against him and Caupo helped to conquer and destroy his own former Castle of Turaida in 1212. The castle was rebuilt two years later as a stone castle that is well preserved even today. Caupo participated in a crusader raid against the still pagan, related Finnic-speaking Estonians and was killed in the Battle of St. Matthew's Day in 1217 against the troops of the Estonian leader Lembitu of Lehola.

|

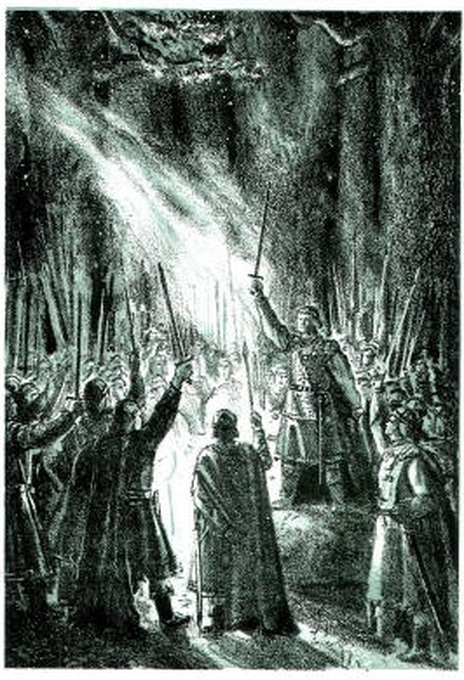

The leader of the Livonian resistence, the only one about whom some biographical information is known, was Lembitu of Lehola, the killer of the traditor Caupo of Turaida. Troops led by Lembitu destroyed a troop of missionaries in the historical Estonian county of Sakala and made a raid as far as Pskov, then a town of the Novgorod Republic. In 1215, Lembitu stronghold (situated near the present town of Suure-Jaani) was taken by Germans and Lembitu was taken prisoner. He was released in 1217. Lembitu aim was to unite the Estonians in order to withstand the German conquest. He managed to assemble an army of 6,000 Estonian men from different counties, but was mortally wounded in the Battle of St. Matthew's Day in September, 1217. The dying leader persuades his people to fight for their freedom. |

In 1207 Emperor Philip's investing Albert and Livonia as a fief and principality of the Holy Roman Empire with Riga as capital and Albert as prince. The surrounding areas of Livonia also came under levy to the Holy Roman Empire.To promote a permanent military presence, territorial ownership was divided between the Church and the Order, with the Church taking Riga and two thirds of all lands conquered and granting the Order, who had sought half, a third.

Courtyard of the Dom Church, cornerstone laid 1211 Albert had ensured Riga's commercial future by obtaining papal bulls which decreed that all German merchants had to conduct their Baltic trade through Riga. In 1211, Riga minted its first coinage, and Albert laid the cornerstone for the Riga Dom. The rebellion was not truly killed as an alliance of tribes failed to take Riga. In 1212, Albert led a campaign to compel Polotsk to grant German merchants free river passage. Polotsk conceded Kukenois and Jersika, already captured in 1209, to Albert, recognizing his authority over the Livonians and ending their tribute to Polotsk. Riga's rapid economic growth prompted its withdrawal from Bremen's jurisdiction to become an autonomous episcopal see in 1213. The oldest parts of Riga were devastated by fire in 1215.

In 1220 Albert established a hospital under the Order for the poor sick: Riga's hospital for the indigent sick. In 1225 it became a Holy Ghost Hospital of Germany, a lepers' hospital, although no cases of leprosy were ever recorded there. In 1330 it became the site of the new Riga Castle.

Albert's knitting of ecclesiastical and secular interests under his person began to fray. Riga's merchant citizenry chafed and sought greater autonomy; in 1221 they acquired the right to independently self-administer Riga and adopted a city constitution. That same year Albert was compelled to recognize Danish rule over lands they had conquered in Estonia and Livonia. This setback dated to the Archbishop of Bremen's closure of Lübeck—then under Danish suzerainty—to Baltic commerce in 1218. Fresh crusaders could no longer reach Riga, which continued to be under threat from the Livonians, now becomed rebels. Albert was compelled to seek assistance from King Valdemar of Denmark, who had his own designs on the eastern Baltic, having occupied Oesel (the island of Saaremaa) in 1203. The Danes landed in Livonia, built a fortress at Reval (Tallinn), and conquered both Estonian and Livonian territory, clashing with the Germans—who even attempted to assassinate Valdemar. Albert was able to reach an accommodation a year later, however, and in 1222 Valdemar returned all Livonian lands and possessions to Albert's control. Albert's difficulties with Riga's citizenry continued. With papal intervention, a settlement was reached in 1225 whereby they ceased to pay tax to the Bishop of Riga and acquired the right to elect their magistrates and town councilors. Albert tended to Riga's ecclesiastical life, consecrating the Dom Cathedral, building St. Jacob's Church for the Livonians' use, outside the city wall, and founding a parochial school at the Church of St. George, all in 1226. He also vindicated his earlier losses, conquering Oesel in 1227, and saw the solidification of his early gains as the city of Riga concluded a treaty with the Principality of Smolensk giving Polotsk to Riga. Albert died in January, 1229. While he failed his aspiration to be anointed archbishop the German hegemony he established over the Baltics would last for seven centuries.

Riga served as a gateway to trade with the Baltic tribes and with Russia. In 1282 Riga became a member of the Hanseatic League. The Hansa developed out of an association of merchants into a loose trade and political union of North German and Baltic cities and towns. Due to its economic protectionist policies which favored its German members, the League was very successful, but its exclusionist policies produced competitors. Back in 1298 citizens of Riga and Lithuanian Grand Duke Vytenis concluded a treaty, whereby pagan Lithuanian garrison would defend them from the depredations of Teutonic Order. The military contract remain in force until 1313. Hansa's last Diet convened in 1669, although its powers were already weakened by the end of the 14th century, when political alliances between Lithuania and Poland and between Sweden, Denmark and Norway limited its influence. Nevertheless, the Hansa was instrumental in giving Riga economic and political stability, thus providing the city with a strong foundation which endured the political conflagrations that were to come, down to modern times. As the influence of the Hansa waned, Riga became the object of foreign military, political, religious and economic aspirations.

Riga accepted the Reformation in 1522, ending the power of the archbishops. In 1524, a venerated statue of the Virgin Mary in the Cathedral was denounced as a witch, and given a trial by water in the Daugava River. The statue floated, so it was denounced as a witch and burnt at Kubsberg.

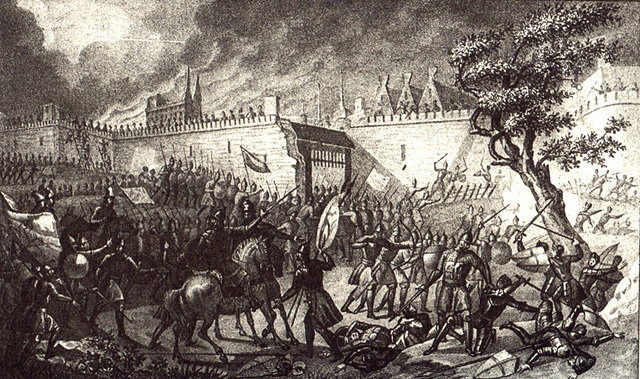

From 1558 to 1583 the Livonian territory suffered the years of war. The Livonian War was fought for control of Old Livonia (in the territory of present-day Estonia and Latvia) when the Tsardom of Russia faced off against a varying coalition of Denmark–Norway, the Kingdom of Sweden, the Union (later Commonwealth) of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland. During the period 1558–1578, Russia dominated the region with early military successes at Dorpat (Tartu) and Narva. Russian dissolution of the Livonian Confederation brought Poland–Lithuania into the conflict while Sweden and Denmark both intervened between 1559 and 1561. Swedish Estonia was established despite constant invasion from Russia and Frederick II of Denmark bought the old Bishopric of Ösel–Wiek, which he placed under the control of his brother Magnus of Holstein. Magnus attempted to expand his Livonian holdings to establish the Russian vassal state Kingdom of Livonia, which nominally existed until Magnus' defection in 1576. In 1576, Stefan Batory became King of Poland as well as Grand Duke of Lithuania and turned the tide of the war with his successes between 1578 and 1581, including the joint Swedish–Polish–Lithuanian offensive at the Battle of Wenden. This was followed by an extended campaign through Russia culminating in the long and difficult siege of Pskov. Under the 1582 Truce of Jam Zapolski, which ended the war between Russia and Poland–Lithuania, Russia lost all its former holdings in Livonia and Polotsk to Poland–Lithuania. The following year, Sweden and Russia signed the Truce of Plussa with Sweden gaining most of Ingria and northern Livonia while retaining the Duchy of Estonia.

With the demise of the Livonian Order during the Livonian War, Riga for twenty years had the status of a Free Imperial City of the Holy Roman Empire before it came under the influence of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth by the Treaty of Drohiczyn, which ended the war for Riga in 1581. In 1621, during the Polish–Swedish War (1621–1625), Riga and the outlying fortress of Daugavgriva came under the rule of Gustavus Adolphus, King of Sweden, who intervened in the Thirty Years' War not only for political and economic gain but also in favour of German Lutheran Protestantism. During the Russo-Swedish War (1656–1658), Riga withstood a siege by Russian forces. Riga remained the largest city in Sweden until 1710 during a period in which the city retained a great deal of self-government autonomy. In that year, in the course of Great Northern War, Russia under Tsar Peter the Great besieged Riga. Along with the other Livonian towns and gentry, Riga capitulated to Russia, largely retaining their privileges. Riga was made the capital of the Governorate of Riga (later: Livonia). Sweden's northern dominance had ended, and Russia's emergence as the strongest Northern power was formalised through the Treaty of Nystad in 1721.

By the end of the 19th. century Riga had become one of the most industrially advanced and economically prosperous cities in the entire Empire, and of the 800,000 industrial workers in the Baltic provinces, over half worked there. By 1900, Riga was the third largest city in Russia after Moscow and Saint Petersburg in terms of numbers of industrial workers. During these many centuries of war and changes of power in the Baltic, the Baltic Germans in Riga, successors to Albert's merchants and crusaders, clung to their dominant position despite demographic changes. Riga even employed German as its official language of administration until the imposition of Russian language in 1891 as the official language in the Baltic provinces. All birth, marriage and death records were kept in German up to that year. Latvians began to supplant Germans as the largest ethnic group in the city in the mid-19th century, however, and by 1897 the population was 45% Latvian (up from 23.6% in 1867), 23.8% German (down from 42.9% in 1867 and 39.7% in 1881), 16.1% Russian, 6% Jewish, 4.8% Polish, 2.3% Lithuanian, and 1.3% Estonian. By 1913 Riga was just 13.5% German. The rise of a Latvian bourgeoisie made Riga a center of the Latvian National Awakening with the founding of the Riga Latvian Association in 1868 and the organization of the first national song festival in 1873. The nationalist movement of the Young Latvians was followed by the socialist New Current during the city's rapid industrialization, culminating in the 1905 Russian Revolutionled by the Latvian Social Democratic Workers' Party.

The 20th century brought World War I and the impact of the Russian Revolution to Riga. The German army marched into Riga in 1917. In 1918 the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed giving the Baltic countries to Germany. Because of the Armistice with Germany (Compiègne) of 11 November 1918, Germany had to renounce that treaty, as did Russia, leaving Latvia and the other Baltic States in a position to claim independence. After more than 700 years of German, Swedish and Russian rule, Latvia, with Riga as its capital city, declared its independence on 18 November 1918.

Between World War I and World War II (1918–1940), Riga and Latvia shifted their focus from Russia to the countries of Western Europe. A democratic, parliamentary system of government with a President was instituted. Latvian was recognized as the official language of Latvia. Latvia was admitted to the League of Nations. The United Kingdom and Germany replaced Russia as Latvia's major trade partners. As a sign of the times, Latvia's first Prime Minister, Kārlis Ulmanis, had studied agriculture and worked as a lecturer at the University of Nebraska in the United States of America. Riga was described at this time as a vibrant, grand and imposing city and earned the title of "Paris of the North" from its visitors.

There then followed World War II, with the Soviet occupation and annexation of Latvia in 1940; thousands of Latvians were arrested, tortured, executed and deported to labor camps in Siberia, where the survival rate equaled that of Nazi concentration camps, following German occupation in 1941–1944. The Baltic Germans were forcibly repatriated to Germany at Hitler's behest, after 700 years in Riga. The city's Jewish community was forced into a ghetto in the Maskavas neighbourhood, and concentration camps were constructed in Kaiserwald and at nearby Salaspils. In 1945 Latvia was once again subjected to Soviet domination. Many Latvians were deported to Siberia and other regions of the Soviet Union, usually being accused of having collaborated with the Nazis or of supporting the post-war anti-Soviet Resistance.

Forced industrialization and planned large-scale immigration of large numbers of non-Latvians from other Soviet republics into Riga, particularly Russians, changed the demographic composition of Riga.

High-density apartment developments, such as Purvciems, Zolitūde, and Ziepniekkalns ringed the city's edge, linked to the center by electric railways. By 1975 less than 40% of Riga's inhabitants were ethnically Latvian, a percentage which has risen since Latvian independence. In 1986 the modern landmark of Riga, the Riga Radio and TV Tower, whose design is reminiscent of the Eiffel Tower, was completed. |